Professor Hellmuth Bott

If one were to ask Professor Helmuth Bott, the director of Porsche's research and development division, to name his favorite car, his answer - aside from the fact that he is a keen collector of VW Beetles - would consist of just one three-digit number: "959".

The project was officially launched on January 21, 1983 when, at the request of Professor Helmuth Bott, the engineer Manfred Bantle

was appointed as project leader. Bantle took precisely one week to

produce an outline specification, setting out the aims of the project

in terms dictated solely by technical considerations, regardless of

the cost or the work involved.

Prior to this, a good deal of thought and discussion had already

been devoted to the design of the new vehicle. One of the principal

reasons for setting up the project was the situation prevailing at the

time in motor mclng, which Porsche had always regarded as having

both a pace-making function for technical innovation and a vital

significance for the image of its road-going cars.

The FIA (Federation Internationale de I'Automobile) in Paris had

introduced a revised version of the Group B rules, with the aim of

encouraging more manufacturers to participate in motor sport. In

Group C, Porsche remained more or less unbeaten for several years:

it was only in 1986 that Jaguar succeeded in catching up with the

cars from Zuffenhausen. The rules for Group A, stipulating

limousine-type dimensions and a production run of at least 5,000

units in twelve consecutive months, made it difficult for Porsche to

Group B, however, for which manufacturers were

required to build a minimum of 200 identical vehicles, seemed to offer interesting new possibilities.

It was to be expected that a considerable number of firms would be sending new and technically advanced vehicles onto the racetrack.

As Helmuth Bott commented later, 'One is always wiser after the event. Audi, Lancia, Peugeot, Renault, Leyland, Citroen and Ford

switched to rallying with their Group B cars, and the Ferrari GTO

will probably never be seen on a racetrack.'

However, at the time when the new rules came into force, there seemed to be a great future in store for Group B cars on the racing circuit, and Porsche was ready and willing to take up the challenge.

But once again, its manufacturing rivals refused to join in the

bidding, or went over to competing in World Rally Championship

events.

"The World Rally Championship never featured on our agenda.

Some time ago, we did take part in a few events, such as the Monte Carlo Rally (which we won three times) and the East African Safari,

but the expenditure involved in competing right through the season

was astronomical. It is also the case that the highly specialized

technical lessons which one learns from this form of motor sport

only have a limited usefulness for the development of our production vehicles.'

Nevertheless, Helmuth Bott makes no secret of the fact that he would have liked to enter the completed car in at least one 'classic' rally, "just to see what our placing would be'. However, the discussions which took place at Porsche in 1982 and early 1983 were still concerned with the future of the Group B car. Following the decision to equip the new vehicle with four-wheel drive, the 924/944 and 928 series were eliminated from Porsche's

plans: 'If the engine is located at the front and the gearbox at the

min back, then the problem of delivering traction to the front wheels

becomes impossible to solve in a way which conforms to our requirements."

Only two alternatives remained: either to develop an entirely new vehicle, or to base the Group B car on the 911. And since there was no question of asking the 200 customers to accept a racing car in disguise, Porsche opted for the 911 solution.

The plans to build a mid-engined car were therefore dropped. A vehicle of this kind - being little more than a racing car with a road license - would have had several disadvantages. It would have been cramped, noisy, loud and uncomfortable; and for drivers unaccustomed to handling such high-performance cars, its handling would have taken a lot of getting used to.

Even if the Executive Board had been able to foresee the customers' enthusiastic reaction to the project, the idea of building a midengined rear-drive car would still have been rejected. However, it was not finally abandoned until mid-1983.

While Manfred Bantle and his colleagues were working out a detailed specification in the spring of 1983, carefully examining all the ideas and suggestions to date - following the first project Conference on 21 February with the departmental heads Peter Falk, Hans Mezger,Paul Hensler and Helmuth Bott, all the departments had been officially brought into the decision-making process -- it became clear to all concerned that the 959 represented an ideal testbed for assessing the future of the 911. And at the same time, it became apparent that this, tile oldest series in the Porsche stable, still had a tremendous unexplored potential.

The first results of the engineers'calculations began to arrive on the project leader's desk. Copies of the provisional specification were circulated on 8 March 1983, and twelve days later, Helmuth Bott had to say goodbye to one of his most cherished designs.

"The C 20 - that was the works name of the car - was a 911 which had been experimentally fitted with four-wheel drive. Since we always try out all sorts of ideas, we had been building occasional examples of the 911 with this form of traction for years, but the C 20 was a particular success. Which, no doubt, was why it was selected for the Paris-Dakar Rally endurance test the following year.' By entering the car in this gruelling desert race, Porsche avoided breaking the rule prohibiting Group B cars from taking part in World Rally Championship events.

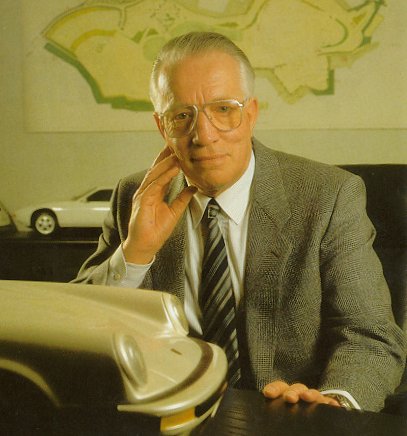

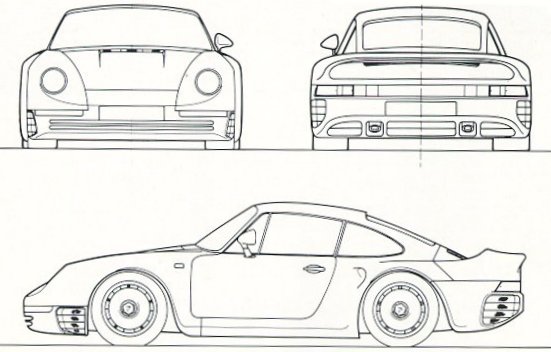

The 959 as it appeared on the drawing board

MAIN 959 PAGE

MAIN PORSCHE PAGE